Structural and Forensic Developments in Securities Litigation

Jonathan Beach*

Significant investment and finance litigation in Australia is principally pursued through a class action mechanism in the Federal Court of Australia and the Victorian and New South Wales Supreme Courts. Such a mechanism has been used for shareholder class actions, managed investment scheme class actions and cartel class actions. The applicable legislative model[1] presupposes the use of an open class, with an opt out mechanism. But more recently, closed classes have been used with group members signed up to litigation funding agreements. The closed class mechanism has been encouraged if not required by external litigation funders to avoid “free riders” and to inject more certainty into case specific funding models.

In the UK, there is no general statutory regime for class actions. The main collective redress procedure is a group litigation order, allowing for the grouping and hearing together of similar individual claims or their common issues; it is a type of opt in mechanism. But since 2015, a statutory regime has also been in place for a class action mechanism for cartel claims heard in the Competition Appeal Tribunal. The UK also has the traditional representative order mechanism, but it has limited utility (as in Australia) because of “same interest” strictures.

Major investment and finance litigation usually involves multiple claimants by reason of the scope of, and ripple effects associated with, contravening corporate conduct. It is for this reason that, apart from regulatory enforcement action, large securities litigation in the Federal Court is generally conducted through class actions. Of the approximately 60 presently active class actions in the Federal Court, 95% are of a commercial nature including:

- misleading or deceptive statements in or material omissions from prospectuses;

- non-disclosure of material information to listed secondary securities market(s) such as the Australian Stock Exchange;

- misleading or deceptive conduct by issuers of structured financial products and ratings agencies (particularly their ratings of synthetic collateral debt obligations and the like);

- unconscionability and penalty recovery claims in respect of bank fees;

- breaches of National Credit Code requirements on lending practices;

- breaches of disclosure requirements in relation to managed investment schemes including the failure to disclose “significant risks”;

- consumer claims dealing with product liability, for example defective medical devices and more recently claims concerning Volkswagen’s emission controls.

But it should be noted that not all such litigation has invoked the class action mechanism. For example, the litigation against ABN AMRO Bank NV and Standard and Poor’s (McGraw Hill International (UK) Ltd) proceeded in the Federal Court as individual claims by local government authorities for misleading or deceptive conduct and negligent misrepresentation concerning the issuing and rating of “Rembrandt” notes (these were structured financial products known as constant proportion debt obligations (CPDO), themselves based on synthetic credit default swap contracts).

There is one other preliminary point that I would make before discussing specific issues of mutual interest. Procedures and mechanisms in US class actions have been and continue to be influential in this area. Now I do not just mean by that that the spectre of US style litigation has been raised as something to be avoided, such that Australian and UK legislative models have evolved to avoid its perceived excesses. Rather I am talking about more tangible considerations. First, US forensic statistical techniques have been usefully applied in Australian shareholder and cartel class actions. Second, some claimants in Australia have sought to invoke US oral discovery mechanisms under 28 USC § 1782 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to obtain information for use in Australian class actions; such conduct was recently enjoined under an anti-suit injunction made by the Full Federal Court (Jones v Treasury Wine Estates Ltd [2016] FCAFC 59). Third, to the extent that a class action regime in either the UK or Australia is perceived to be inadequate, claimants may perceive that litigating in the US may be more attractive, subject to forum non conveniens questions or problems associated with “f-cubed” transactions (i.e. in US proceedings, foreign claimants seeking to sue a foreign issuer in relation to a transaction which occurred in a foreign country). Both UK and Australian lawyers have an interest in nurturing the first issue and discouraging the second and third strategies.

It is now convenient to turn to structural issues and then to compare types of claims that are pursued in securities litigation in Australia and the UK, to discuss causation and loss and damage and then to make some observations on cartel class actions. Finally, I will discuss the use of assessors.

Structural issues

Group proceedings

Given the nature and scope of investment and finance litigation, usually it is preferable that individual claims be grouped. This has the advantage of achieving economies of scale and is conducive to the pursuit of proceedings that might not be affordable or viable if claims were only pursued individually.

But there are other advantages. First, class actions are of benefit to a defendant. They avoid the cost and expense of having to defend the same allegations in multiple actions. Further, the problem with inconsistent findings in multiple actions is avoided; this is an actual problem for the litigants and also a broader perception problem. Generally, a defendant can draw a line under its exposure and liability for past events, which is of advantage to both a defendant and its insurer. Second, from the perspective of the administration of justice there are other advantages. The grouping facilitates an efficient use of judicial resources.

More specifically, in the context of investment and finance litigation, class actions can have a disciplining effect on corporate behaviour in terms of specific and general deterrence. A firm may apprehend that one of the principal consequences of non-compliance with the law is the consequences and incidences of class actions: the costs of litigation, the payment of substantial compensation and significant reputational harm. Such perceived consequences may discipline the firm who contravened and act as a deterrence against re-offending. Such perceived consequences may also discipline the behaviour of other firms who may be tempted to engage in similar conduct. But “over-deterrence” may arise where claims of doubtful merit are made but a defendant nevertheless desires to settle to avoid even the slight risk of massive exposure. Further, the deterrence effect may be weakened by other considerations. For example, a defendant may be able to pass on to its customers the financial consequences of its wrongdoing. Further, the existence of insurance may weaken the deterrent effect. Further, any judgment may be against the corporate defendant rather than against the individual(s) who was responsible. Relatedly, current shareholders may ultimately bear the loss rather than the principal wrongdoer.

In Australia, although the corporate regulator, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, can take relevant enforcement proceedings including seeking civil pecuniary penalties, class actions and a defendant’s exposure thereto appear to have had a more disciplining effect on corporate and market behaviour, particularly in relation to informational disclosures. In one sense ASIC has stepped back and allowed private enforcement mechanisms to be used. This has partly been a function of the allocation of scarce resources.

Open and closed classes

The statutory model applying to Federal Court class actions generally provides for an “opt out” mechanism or open class. The benefits of an open class model allow for and encompass all group members, unless they choose to opt out. So, all affected persons receive the benefit of the class action unless they make the positive choice to opt out and to separately pursue their own individual claim. Such a mechanism does not meaningfully impinge on individual autonomy as group members are notified of their right to opt out. Moreover, if they choose not to opt out they can essentially act as free riders until after the determination of the common issues, subject to one matter that I will discuss concerning “common fund” orders.

But because of different funding mechanisms, closed classes have recently been more frequently used; these are not precluded by the statutory regime. Litigation funders have preferred closed classes with all members signed up so that their financial investment in the litigation is protected and there are no free riders. But this has the downside that those who have not signed up but are otherwise putative group members are excluded and do not receive the benefit of the class action.

Contrastingly, in the UK, instead of a general class action scheme, a sector by sector approach has been adopted. Presently, only the competition law sector has a statutory class action model.

The Consumer Rights Act 2015 (UK) by Schedule 8 has introduced class actions provisions into the Competition Act 1998 (UK) adding, inter alia, ss 47B to 47E, 49A and 49B. The provisions would appear to relate only to proceedings in the Competition Appeal Tribunal. They contain the following elements:

- Collective proceedings are allowed to be brought by a representative on behalf of the class combining two or more claims that raise the same, similar or related issues of fact or law and that are suitable to be brought in collective proceedings;

- There is, in essence, a preliminary certification process such that collective proceedings may be continued only if the Tribunal makes a collective proceedings order (s 47B(4));

- The Tribunal is empowered to choose whether the proceedings should be “opt in” or “opt out” collective proceedings (this latter option is not available in relation to a class member who is not domiciled in the UK).

It would seem that these provisions were introduced in an environment where levels of enforcement were low and, relatedly, the “same interest” requirement of the representative procedure rule 19.6 was a substantial impediment to that procedure being used for cartel cases (Emerald Supplies Ltd v British Airways plc [2011] 2 WLR 203); one reason was that the availability of the pass through defence as against some claims for damages but not others meant that the claimants did not all have the same interest in the action.

Funding

There has been considerable growth in Australia of external litigation funders. In Australia, there is no champerty or maintenance problem (Campbells Cash and Carry Pty Ltd v Fostif Pty Ltd (2006) 229 CLR 386). As the price for funding the lead plaintiff’s legal expenses, providing security for costs sought by a defendant and indemnifying the lead plaintiff against any adverse costs order, litigation funders under contractual arrangements with individual group members have usually procured fees between 25 to 45% of the damages recovered. Litigation funding usually takes this form rather than before the event or after the event insurance.

In Australia, litigation funders are largely unregulated; moreover, there is no voluntary industry code of conduct. Funders are exempt from regulatory requirements under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) applying to the registration of managed investment schemes, provided that they maintain adequate procedures for managing conflicts of interest including making appropriate disclosures. Conflicts can arise between any two or more of the funder, the lead plaintiff, group members and the lawyers in terms of decisions relating to either the prosecution of a proceeding or its settlement. Whether litigation funders should be licensed or whether capital adequacy requirements should be imposed has been the subject of consideration by the Commonwealth government.

Litigation funding has produced the following outcomes. First, there has been a proliferation of closed class proceedings. Second, the subject matter of class actions has shifted from product liability claims to securities actions (e.g. shareholder class actions). One reason is due to the economics. In terms of the aggregate quantum claimed, this is likely to be larger for shareholder class actions. Second, it may be thought that it is easier to establish liability for material non-disclosure claims. After all, when negative news is published to the market by a listed company and its share price plummets, plaintiffs’ lawyers’ intuition is to question whether there has been timely disclosure and to assume that there is a ready-made prima facie case of breach of the applicable normative standard. A third factor is that there is perceived to be a very high settlement rate (indeed no shareholder class action as such has proceeded to judgment). This is attractive to plaintiffs’ lawyers and external funders. The high settlement rate has been partly attributed to uncertainty over the viability of market-based causation. Whether such a settlement rate is maintained remains to be seen.

There is one other new development on funding that is worth mentioning at this point, being “common fund” orders.

A “common fund” order permits costs and expenses and any external funder commission to be deducted from each group member’s damages (or settlement amount) irrespective of whether they have consented or signed up to a litigation funding agreement. Such an order is said to avoid the “free rider” problem. It arises in the context of open classes or “opt out” style proceedings. It does not arise in closed classes as usually it is a condition of membership of the closed class that each group member has signed a litigation funding agreement. The idea of a “common fund” approach is that each group member equally share (as the beneficiaries) the burden of the costs and expenses incurred in order to obtain the fund. In essence the external funder also gets its commission from these non-consenting group members. In Australia, it is accepted that there is power to make such an order but as yet they have only been made at a late stage of proceedings to facilitate settlement and then on the basis of non-opposition.

Another type of order that has been made involves a “funding equalisation” formula. It differs from a “common fund” order in that although all group members are compelled to equally share the burden of the relevant costs and expenses, the external funder gets little if any additional commission from the non-consenting group members. The way it works is as follows, simply put. Let us assume that part of the class has signed up to pay X% commission to the funder, and part of the class have not signed up to pay that commission. Say there is an overall settlement of the action. What occurs is that for each group member who signed up to pay commission of X%, that amount gets paid to the funder. But for each group member who did not sign up, X% is still subtracted from their share, but this time it is added back to the pool for distribution pro rata to all group members; it is not siphoned off to the funder. This method achieves the equalisation required but without delivering any substantial additional benefit to the funder.

Should a “common fund” order be made at the inception of an “opt out” class action? It is said that this will inter alia encourage open class actions and avoid the problem of closed classes including competing class actions. A Full Court of the Federal Court has currently reserved judgment on that question.

Finally on funding related topics, I should note that Australian lawyers are not allowed to charge contingency fees. However, by having an equity interest in an external litigation funder, whether directly or through a related entity, some lawyers have achieved indirectly what they could not achieve directly. But Australian lawyers can enter into conditional fee arrangements (e.g. “no win, no fee”) and in some States obtain a 25% uplift on their professional costs.

Suing directors and auditors

In Australia in shareholder class actions, usually only the corporate defendant is sued. It is usually listed and therefore taken to be sufficiently financially sound to meet any claim. Moreover, the compounding difficulties associated with suing multiple defendants is avoided. Further, the principal statutory provision relied upon (s 674 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)) is not a proportionate liability provision.

But occasionally it has been thought desirable to sue directors to obtain external funds to meet the claims from any directors’ insurance. But usually the company and its directors are insured under a group policy, so by suing the company you would effectively have this access anyway. Moreover, with the usual aggregation provision and the total policy limit being theoretically available to meet a claim against any one or more co-insured, there is usually no additional advantage in separately suing the directors.

There have also been some occasions where auditors have been sued by the class. This can also provide a source of external funds to meet investors’ claims. But usually the representative party has eschewed such problematic and complex claims where solvency or the capacity to pay is not in issue. Auditors, nevertheless, may be joined as third parties by the corporate defendant.

Finally, in the context of shareholder class actions it should be noted that in suing the company, claimants who are continuing shareholders are in essence and in part suing themselves, albeit that they would in part be effectively subsidised by the other continuing shareholders who were not claimants. Such a consequence may also provide an impetus for pursuing other parties as a source of external funds, although it is not usually the primary motivation.

The different claims

The principal statutory causes of action invoked in investment and finance litigation in Australia and the UK have their differences. But underpinning them are similar concepts dealing with:

- questions of market disclosure and the issue of materiality;

- questions of causation;

- the calculation of loss and damage.

It is appropriate to first discuss the Australian context.

The Australian context

A company’s non-disclosure to the market of material information affecting its share price is the central element of any shareholder class action. The principal statutory provision relevant to shareholder class actions is s 674 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), which is the continuous disclosure provision. But some actions also involve misleading or deceptive conduct allegations invoking s 1041H of that Act and s 12DA of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth). Misleading or deceptive conduct claims focus on announcements, reports or accounts published by the company that contain misleading or deceptive content or, in context, amount to misleading or deceptive conduct by omission. Such announcements, reports or accounts can be looked at in two causation contexts. First, they may feed into what material was available to and in the market place, and which therefore was factored into the share price; so they may relate to the s 674 case. Second, they may be the subject of separate focus as to whether their contents came to the attention of, or were read by, actual or potential investors in the company’s shares, and therefore had a more direct causal effect on such investors’ behaviour, so providing a foundation for a misleading or deceptive conduct case. For present purposes I will only focus on s 674.

The elements of s 674 are that:

(a) The company must be a “listed disclosing entity” and must be bound by continuous disclosure obligations under applicable listing rules, relevantly here the Australian Stock Exchange Listing Rules;

(b) The company has to have information that the Listing Rules require be disclosed to the ASX. And in elaboration and relevant to Listing Rule 3.1, there has to be “information” that the company must be “aware” of that a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value of the shares (with no exception to disclosure under Listing Rule 3.1A applying). Moreover, assuming that Listing Rule 3.1 requires disclosure, nevertheless if the information is “generally available”, then no disclosure is required. Further, but overlapping the Listing Rule 3.1 requirement, s 674(2)(c)(ii)[2] expressly states that a reasonable person must expect the information to have a material effect on the price or value of the shares as elaborated by s 677.

Let me focus in on the question of materiality of the relevant information. Materiality arises in a number of contexts.

First, it is embedded in ss 674(1) and 674(2)(b) itself, which requires reference to Listing Rule 3.1 of the ASX Listing Rules. Listing Rule 3.1 in turn refers to information that “a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value” of the relevant shares.

Second, and relatedly, it is expressly referred to in s 674(2)(c)(ii) in similar terms. This is elaborated on in s 677, which refers to information that would, or would be likely to, “influence persons who commonly invest in securities”. Section 677 provides a sufficient condition for establishing the s 674 materiality, but it is not expressed to be a necessary condition.

Third, materiality arises separately in dealing with causation. The first two contexts refer to a reasonable person’s expectation of materiality. But in the general causation context (as opposed to individual investors’ actions or failures to act on the basis of information or the absence of information) where one is seeking to ascertain the effect of information or its non-disclosure on share price, what I would describe as objective materiality arises. In other words, did the non-disclosure of adverse information produce share price inflation? Did the non-disclosure of favourable information produce share price deflation? I will address this context in a moment.

Now in terms of the first two contexts, the headline test is objective and not focused on individual subjective states of mind. But how is this objective test established forensically? Usually evidence will be sought to be adduced in the following manner:

(a) One will have the direct evidence of the representative party to establish its individual causation case.

(b) One may have evidence from large institutional or wholesale investors (including fund managers) as to their expectation of materiality; this is relevant given the genus of the class referred to in s 677. Now to say that the evidence of institutional investors may be relevant to materiality and its statutory elaboration in s 677 is not to limit materiality and the operation of s 677 to any particular genus narrower than the breadth of the statutory language used, being “persons who commonly invest in securities”, which may include the small or large, sophisticated or unsophisticated, or retail or wholesale investor. Rather, it is simply to recognise that such evidence is relevant, whatever the breadth the language of s 677 can accommodate. To say that materiality and s 677 is not a subjective test is not to deny that evidence of institutional investors’ behaviour and perceptions can inform the application of the objective test. In terms of the breadth of s 677, this has recently been dealt with by the Full Federal Court in Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Ltd (in liq) (2016) 330 ALR 642 at [97] to [116].

(c) One may have expert evidence from brokers, analysts, investment bankers and capital market researchers opining on the question of materiality and expectation; this is more indirect than category (b) evidence.

(d) One will have evidence, at least on the causation question, on the purely objective materiality question i.e. whether the information and its non-disclosure actually produced share price inflation or deflation. Alternatively expressed, if on the day the information is disclosed to the market there is a statistically significant movement in the share price that can be attributed to the disclosed information, then this provides some evidence of materiality. But the absence of such evidence does not mean that one cannot establish the relevant s 674(2)(c)(ii) expectation as illuminated by s 677. Section 677 is not a high threshold. The terms of s 677 do not invite any inquiry as to whether any change in the price of securities has occurred caused by an announcement. Nevertheless what happened in the market, in terms of movements in share price, may assist the Court in applying the relevant test; such an analysis is an ex post analysis, albeit that the expectation issue is an ex ante one.

There is a related debate as to whether institutional investors make investment decisions employing different methodologies and resources than retail investors; see Earglow Pty Ltd v Newcrest Mining Ltd (2015) 230 FCR 469. Some institutional investors have access to specialised internal research capabilities, proprietary financial models and experienced global resources which enable such investors to carry out in depth industry analysis, not available to retail or small investors, to inform their investment making decisions.

There is academic support for such a difference. Qualitative and quantitative research techniques have arguably illustrated the distinction between institutional investors and retail investors. See for example Schnatterly, K, Shaw, K and Jennings, W “Information Advantages of Large Institutional Owners” (2008) 29 Strategic Management Journal 219 at 219, 220 and 225; Grossman, S and Stiglitz, J “On the Impossibility of Informationally Efficient Markets” (1980) 70 American Economic Review 393; Bushee, B and Goodman, T “Which Institutional Investors Trade Based on Private Information About Earnings and Returns?” (2007) 45 Journal of Accounting Research 289; and Parrino, R, Sias, R and Starks, L “Voting with their feet: institutional ownership changes around forced CEO turnover” (2003) 68 Journal of Financial Economics 3 at 8.

Further, there is literature which supports the proposition that it is institutional rather than retail investors who make trading decisions which impact the market and affect the price of securities and, in turn, the volatility of the market. See for example Harris, L Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners (Oxford University Press, 2003) at 224; Holthausen, R, Leftwich, R and Mayers, D “Large-block transactions, the speed of response, and temporary and permanent stock-price effects” (1990) 26 Journal of Financial Economics 71 at 90; Spierdijk, L “An empirical analysis of the role of the trading intensity in information dissemination on the NYSE” (2004) 11 Journal of Empirical Finance 163 at 172; Basak, S and Pavlova, A “Asset Prices and Institutional Investors” (2012) London Business School – Centre for Economic Policy Research (available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2153561) at 1 and 34; and Keim, D and Madhavan, A “Anatomy of the trading process: Empirical evidence on the behavior of institutional traders” (1995) 37 Journal of Financial Economics 371 at 372.

Let me now discuss the third context of materiality dealing with the objective content and effect of the information on share price rather than a reasonable person’s expectation as to material effect. Assume that the relevant information is disclosed by the company and contemporaneously the share price falls. By those observable facts you might infer the fact of materiality and, accordingly, that the share price had been inflated. Equally, if there has been no share price change at the time of formal disclosure, you might conclude an absence of materiality and consequently no inflation. Alternatively, you might conclude that the market became aware of the information at an earlier time and had already factored it into the share price. So you might have to go back to an earlier time to look at materiality and to assess the inflationary component in the share price.

But this type of “analysis” is at best intuitive perception; it may not be sufficiently rigorous; post hoc, ergo propter hoc reasoning is inadequate. As explained in Dura Pharmaceuticals Inc v Broudo 544 US 336 (2005) at 342–3, there may be a “tangle of factors” affecting share price, including changed economic circumstances, investor expectations, and industry or firm specific facts which may account for price change rather than just the material information disclosed, but which ought to have been disclosed earlier. Moreover, when a company decides to announce material information which ought previously to have been disclosed, the announcement usually contains other information, particularly if a company is aware of the forensic benefits flowing from “mixed” announcements. For example, say a company announces at the one time two types of negative information: first, the negative information that should have previously been disclosed but wasn’t; second, further negative information that has been disclosed in a timely fashion. Say that as a result of such a “mixed” announcement there is a share price fall. Which part of the fall is referable to the first type of information the subject of the contravening conduct? Take another scenario where the “mixed” announcement contains new positive information (disclosed in a timely fashion) with the negative information which ought previously to have been disclosed. Say that as a result of the announcement there is no share price fall. How do you then work out materiality and the inflationary component in the share price solely referable to the tardy disclosure of the negative information?

There are at least two ways to establish objective materiality. First, by a qualitative assessment of the relevant information, where an expert’s qualitative opinion is then overlaid. Second, by a statistical analysis of the movement in the share price when disclosure is made. Such a quantitative technique is more rigorous.

Preferably, the assessment of materiality should use quantitative linear regression techniques involving event studies. These are studies that quantify the effects of information on share price. These techniques have been used since 1969 in US securities fraud litigation. Many US courts have required such studies, e.g. In re Northern Telecom Ltd Securities Litigation 116 F Supp 2d 446 at 460, In re Imperial Credit Industries Inc Securities Litigation 252 F Supp 2d 1005 at 1015–6, In re Executive Telecard Ltd Securities Litigation 979 F Supp 1021, Miller v Asensio & Co Inc 364 F 3d 223 at 234 and In re Oracle Securities Litigation 829 F Supp 1176 at 1181. Such studies are useful in three interrelated contexts, namely, objective materiality, causation and loss and damage.

The essential elements of such studies are the following:

(a) First, you take a market and/or industry share index and obtain data for the movement in that index over a relevant period.

(b) Second, you look at the movement of the share price for the particular company over that same relevant period.

(c) Third, you model the normal relationship of the share price movement for the particular company against the movement of the index that you have chosen over the relevant period. You hope to produce a statistically significant linear trend using regression analysis, so that you can then make predictions as to the company’s share price based upon the movement in the index. I have discussed statistical methods in more detail in “Class Actions: Some Causation Questions” (2011) 85 Australian Law Journal 579.

(d) Fourth, you take the day when (and immediately after) the information is disclosed to the market. At that time you have the actual share price for the particular company immediately after disclosure.

(e) Fifth, you compare this actual share price with what you can predict for the share price based upon the relationship with the movement of the index as referred to in sub-paragraph (c). In essence, you are looking at what you would have predicted for the change in share price on the day by reference solely to normal background or market conditions (economic, general investor market confidence etc). You then compare this predicted share price with the actual share price immediately after disclosure. The difference between the predicted and actual price is then taken to be attributable to the information that was disclosed. If the actual price falls from what you would have predicted (based on normal market movements), then you have established that the share price was inflated by reason of the non-disclosure (but then deflated when full disclosure was made). If the actual price rises from what you would have predicted, then you have established that the share price was deflated by reason of the non-disclosure (but then inflated when full disclosure was made).

Now this is the simple case. But at this point there are various caveats and qualifications to note.

First, event studies rely on the “semi-strong” version of the efficient capital market hypothesis, which states that share prices in an actively traded security reflect all publicly available information and respond quickly to new information. The “strong” form is that prices incorporate both public and private (including inside) relevant information. The “weak” form excludes contemporary information of any sort; present price is taken to reflect only historic price changes. Moreover, share price impacts of an event can only be revealed if the following conditions are present: (a) the event is a well-defined news item; (b) the time that the news reaches the market is known; (c) there is no reason to believe that the market anticipated the news; and (d) it is possible to isolate the effect of the news from market, industry, and other firm specific factors which also simultaneously affect the company’s share price. If you are not able to proceed on the efficient capital market hypothesis and to satisfy these conditions, then you cannot assume that the difference between your actual share price and the predicted share price (based on the relationship of the movement with the index) will give you your inflation/deflation. I will elaborate further on the hypothesis later.

Second, as will be apparent from my simple description, you can only perform the study looking at the time when the announcement is made and you have the actual share price post announcement. You cannot use this “simple” technique if there is nothing announced, and by definition there is no actual share price after the announcement.

Third, you cannot use this simple method where on the day of the announcement there are other idiosyncratic circumstances (i.e. other than the particular information disclosed on that day) that affect only the company’s share price, but not the market generally and therefore the market index. The simple method assumes that the only unusual circumstance on the day is the announcement of the particular information disclosed, which ought to have been disclosed sooner, and nothing else. It attributes the difference between the actual share price and the index predicted share price to the information disclosed and nothing else. But:

(a) If something else has occurred on the day specific to the company and not the market, then this will confound the analysis. The actual share price change (as compared with the index) will be produced by two or more idiosyncratic features which may not be able to be separated. More complex techniques are needed, the discussion of which is beyond the scope of this paper.

(b) Equally, if the announcement is a “mixed” announcement of the type previously suggested, then this will also confound the analysis.

Fourth, you may have a situation where there has been a pattern of non-disclosure over time, where it is found that for successive accounting periods there is an accumulation of undisclosed negative information. Assume that, finally, the true position is revealed and that the corrective disclosure is for the cumulative period. Doing an event study on the final price reaction will not give you the effect of a particular non-disclosure or the inflationary component solely referable thereto. This may have significance for group members who are acquiring and disposing of shares at different times during the cumulative period.

Fifth, there is a further note of caution. Let us assume that you have shown a price difference between the actual and predicted prices. Nevertheless that may not be sufficient. There may be significant volatility in share price movements, including for the shares of the company in question. The particular price movement for the company in question at the time of the announcement must be analysed to see whether it is statistically significant or whether the movement is within normal random variations for the share price. Undoubtedly, the more volatile the share price for the particular company, the less likely that you are to show a movement on the day of the announcement which is of sufficient statistical significance to be attributable to the announcement, as distinct from movement within the random volatility parameters for the shares in question. Equally, if the stock market itself is going through a particular period of volatility, you may have a problem on the other side of your equation.

Sixth, earlier I have referred to assessing the index over the relevant period and determining the relationship of the movement in the company’s share price to the movement in the index. What “relevant period” do you use? Some methods would just use an index for a period before the announcement and look at the relationship of the movement in that index against the movement in the company’s share price over that time. So, for example, and perhaps usually, you might use an estimation window of one year. Other methods would actually also include data after the corrective disclosure to anchor the index with the company’s “true” share price; at that time the share price will have the inflation or deflation removed. Another aspect to consider is whether you use any data at all for the period of the contravention. Some models use only data for the index and data for the company’s share price before the contravening non-disclosure period. Other models would also include within period data. It is unnecessary to elaborate further for present purposes.

Seventh, as I have said one matter that will need to be established on the evidence is the “semi-strong” version of the efficient capital market hypothesis. I accept, of course, that an event study may itself show one aspect that in and of itself partially supports demonstrating market efficiency, that is, the speed of the apparent cause and effect relationship between an unexpected event or financial release and a response in the share price.

Generally, reference may have to be made to the well-known proxy factors referred to in Cammer v Bloom 711 F Supp 1264 (DNJ 1989) at 1286 to 1287 for determining market efficiency. These have been supplemented (see for example Krogman v Sterritt 202 FRD 467 (ND Tex 2001) at 477 to 478) including looking at the volume and patterns of trading by institutional investors (O’Neil v Appel 165 FRD 479 (WD Mich 1996) at 503).

Further, evidence concerning the behaviour of institutional investors may well be relevant in analysing or establishing any assumption used as to the “semi-strong” version of the efficient capital market hypothesis. Moreover, one may also need to consider how market price is affected by factors other than informational inputs. For example, some large investors may engage in portfolio rebalancing exercises so that their spread of investments matches weightings of stock in an index. Further, they may vary their investments to meet their own liquidity or taxation requirements. Further, market price may be affected not just by human assimilation of information but by computerised trading programs where complex algorithms implement trades on metrics that are pre-determined.

The UK context

For the benefit of the colonial silks attending the conference, I will set out a brief description of what appears to me to be the key UK legislation applicable to the present discussion. Others more knowledgeable will speak on this topic.

The principal UK statute relevant to the context of securities litigation appears to be the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (UK) (the FSM Act). The FSM Act regulates financial services and the operations of securities markets, particularly in England and Wales. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is the primary regulator.

There are two types of litigation. First, one has public securities actions brought by the FCA under criminal and civil regimes applying to, inter alia, insider dealing and market abuse cases. This is not dissimilar to the role played by ASIC under the Corporations Act. Second, one has private securities litigation utilising statutory liability regimes under the FSM Act.

Apparently, private securities litigation in the UK principally relates to causes of action for untrue or misleading statements in prospectuses or listing particulars, including the omission of necessary information from such documents, and for recklessly misleading statements in or dishonest omissions from other material published by listed issuers.

Section 90(1) provides:

(1) Any person responsible for listing particulars is liable to pay compensation to a person who has —

(a) acquired securities to which the particulars apply; and

(b) suffered loss in respect of them as a result of —

(i) any untrue or misleading statement in the particulars; or

(ii) the omission from the particulars of any matter required to be included by section 80 or 81.

There are exemptions in Schedule 10 that I will put to one side. Section 80(1) provides:

(1) Listing particulars submitted to the FCA under section 79 must contain all such information as investors and their professional advisers would reasonably require, and reasonably expect to find there, for the purpose of making an informed assessment of —

(a) the assets and liabilities, financial position, profits and losses, and prospects of the issuer of the securities; and

(b) the rights attaching to the securities.

Section 90 is not a continuous disclosure requirement of the type set out in s 674 of the Corporations Act. It applies to listing particulars. But it would seem arguable that s 90(1) does not necessarily confine any claim to an original purchaser, but may apply to a person who acquires shares in the secondary market. Further, although the concept of materiality is not expressly referred to, one is dealing with akin concepts. In any event, for a cause of action under s 90(1) it may be said that the materiality of information not disclosed would need to be established in order for causation to be established and for the compensation claim to succeed.

Section 90A is of broader application and not confined to the listing particulars. By reference to Schedule 10A it provides more broadly for the liability of issuers of securities to pay compensation to persons who have suffered loss as a result of:

(a) a misleading statement or dishonest omission in certain published information relating to the securities; or

(b) a dishonest delay in publishing such information.

Now the fault element is higher than for s 90. Further, unlike s 90, there would appear to be the need to show reliance (see clause 3 of Schedule 10A). Query whether a US “fraud on the market” type theory could be invoked in this context.

In addition to the FSM Act provisions, s 2(1) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967 (UK) provides:

(1) Where a person has entered into a contract after a misrepresentation has been made to him by another party thereto and as a result thereof he has suffered loss, then, if the person making the misrepresentation would be liable to damages in respect thereof had the misrepresentation been made fraudulently, that person shall be so liable notwithstanding that the misrepresentation was not made fraudulently, unless he proves that he had reasonable ground to believe and did believe up to the time the contract was made the facts represented were true.

It would seem that this could found a cause of action by a purchaser on a secondary market against an issuer, where the issuer made the statement to the original purchaser (Taberna Europe CDO II plc v Selskabet AF1 [2015] EWHC 871 at [105] per Eder J).

I have not discussed Part 8 of the FSM Act dealing with market abuse (insider trading, market manipulation etc) and Regulation (EU) No 596/2014 on market abuse which appears to take effect on 3 July 2016 and will replace parts of Part 8 (ss 118 and 118A). That is for the UK expert speakers to address.

Causation

Causation in shareholder class actions in Australia usually involves the following elements for the “inflationary” case:

(a) A company is said to have contravened the continuous disclosure requirements of Listing Rule 3.1 and s 674 of the Corporations Act, by not disclosing material adverse information to the market.

(b) As a result of such non-disclosure, the listed price for the company’s shares is said to have been inflated i.e. above the price that it would have been if the material information had been disclosed.

(c) Investors have then purchased shares at the inflated price and held them after the time when the price ceased to be so inflated, i.e. when the material information became known to the market. Accordingly, such investors have suffered loss and damage by reason of the contravention.

Other possibilities arise for the “deflationary” case. There could be share price deflation as a result of the non-disclosure of material positive information, i.e. the directors may have withheld favourable information. A cause of action may arise for a shareholder who sold his shares during the deflationary period when the share price was lower than what it would have been if such positive information had been disclosed to the market.

In shareholder class actions, there are various causation possibilities including:

(a) establishing reliance;

(b) satisfying a form of market-based causation; or

(c) invoking the US “fraud on the market” causation theory.

I am proceeding here on the assumption that the information is material in the sense that its non-disclosure has produced share price inflation or deflation which is objectively ascertainable.

In terms of the legal causation test relevant to misleading or deceptive conduct, s 1041I of the Corporations Act requires establishing “loss or damage by conduct of another person”. It has a similar focus to analogous provisions in the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). The word “by” expresses the notion of causation without defining or elucidating it. The statutory test may embrace practical or common sense concepts of causation, but only requires that the contravention be a cause of the loss, in the sense of the contravention materially contributing to the loss, rather than thecause or the predominant cause.

For the s 674 contravention, the legal causation test requires the connecting feature of “resulted from” (see s 1317HA). But how are these legal tests to be applied forensically?

The first causation mechanism, establishing direct reliance, is the conventional means for establishing causation in misleading or deceptive conduct claims. That is, did the relevant shareholder read (or have communicated to him) and rely upon the content of the various published announcements, reports or accounts? And many cases have looked at such reliance questions, which are not common issues but rather specific to individual investors. Now reliance may be a sufficient condition for establishing causation, but is it a necessary condition? It would appear not. The following can be said:

(a) First, the statutory language of “by” does not in and of itself suggest that it is a necessary condition.

(b) Second, although past cases in the misleading or deceptive conduct sphere focus on establishing reliance, that experience does not establish the induction that all such cases must establish it; one explanation for the de facto position may be that reliance was the only causation theory advanced in those cases due to the misplaced bias in favour of importing into the statutory test concepts from common law causes of action.

(c) Third, the “passing off” scenario cases do not suggest that the person having the cause of action need establish any reliance for himself, albeit that the potential for third party reliance is not irrelevant. More generally, cases in other contexts have accepted that reliance is not a necessary condition for causation.

(d) Fourth, and contrary to (a) – (c), it has been said that policy considerations support the view that reliance remains the appropriate test in market-based shareholder class actions. It has been said that if the purpose of implementing the continuous disclosure regime was to assist people to evaluate their investment alternatives and encourage greater research by investors, dispensing with the need to prove reliance would not appear to be consistent with these objectives. But s 1041I(1B) of the Act and s 12GF(1B) of the ASIC Act (the “contributory negligence” style defences) may suggest a policy of not reading down the primary liability causation provisions to necessarily require reliance. But you can flip this argument.

(e) Fifth, a difficulty in the thesis that you need to show reliance arises directly in the misleading or deceptive conduct context where silence is the principal focus. How can a shareholder be said to rely upon unaware undisclosed information? But perhaps this issue can be finessed by saying that you can rely on conduct and circumstances in which the information not disclosed was material, so leading to reliance on the half-truth. But you can see the conceptual difficulties in asserting that reliance is a necessary condition. And this is even more acute when you get into the direct territory of Listing Rule 3.1 and s 674, which is beyond the half-truth scenario. The investor may have read nothing at all but merely assumed that in paying the market price, such a price reflected all information disclosed and disclosable to the market under Listing Rule 3.1. But another way to finesse the reliance question may be to express it nebulously in terms of an investor (or his agent) “relying” upon the integrity of the market and the market price reflecting all such information. But you are then moving into indirect territory and into areas to which the investor may not have turned his mind. But then a broad view of “reliance” may not necessarily require the formation of a positive belief, although the US cases assume that it does, hence their innovative device of the “rebuttable presumption” (see below).

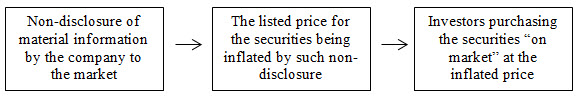

The second causation mechanism, the market-based causation theory, steps outside the classic reliance theory. It involves the following reduced causation chain (for the inflation scenario):

Now various points. First, it is difficult to see how such a causation theory is necessarily excluded by the plain meaning of the statutory language for causation. The language for misleading and deceptive conduct causation is “by”. For a s 674 contravention and the s 1317HA remedy, the wording is “resulted from”, although nothing turns on this difference. Moreover, textual and contextual analysis of the broader statutory framework is not inconsistent with such a theory. And broadening the scope further, gleaning the legislature’s hypothesised singular purpose does not establish a purpose that is inconsistent with the or a market-based causation theory being embedded within the statutory language. The statutory language, subject, scope and purpose so permit. Second, if reliance is not a necessary condition for causation, it implies the inclusion of some market-based causation theory within the statutory language. Third, if it matters, the market-based causation theory is not inconsistent with a “but for” approach (albeit non-comprehensive) or a “common sense” approach (albeit nebulous). Fourth, now it might be said that it is anomalous to entertain a market-based causation theory which permits recovery by investors who knew or ought to have known the true position of the company’s affairs. But actual knowledge may break the chain of causation. Moreover, for misleading or deceptive conduct claims, you do have s 1041I(1B) and s 12GF(1B) available, which consider actual and constructive knowledge. Fifth, it might also be said that permitting such a theory means that, strictly, an investor may have a right to recover even if they did not hold anybelief as to the integrity of the market price (rather than had knowledge or constructive knowledge of the true position). But practically, most investors, if asked, would say that they held such a belief (or at least that their broker or agent held such belief) at the time of acquisition. For those that didn’t have such a belief or would have purchased at the same price even if they knew the true position, again, such circumstances may break or negate any causation chain.

It would seem that so far as Federal Court jurisprudence is concerned, a market-based causation theory is at least reasonably arguable (Caason Investments Pty Ltd v Cao (2015) 236 FCR 322 at [58] to [85] per Gilmour and Foster JJ and at [145] to [158] per Edelman J). Recently, it has been applied in the NSW Supreme Court in the more confined context of a proceeding dealing with an appeal against a liquidator’s rejection of proofs of debt and not involving s 674 of the Corporations Act (In the matter of HIH Insurance Ltd (in liq) [2016] NSWSC 482). But it remains to be seen how an appellate court will finally deal with the matter (apparently there is to be no appeal in the HIH matter) particularly in the context of ss 674 and 1317HA. The causation question must be tailored to and assessed in the context of the specific normative standard applying to the relevant contravening conduct. But there are even stronger arguments for applying a market-based causation theory in the s 674 context.

Further, even a market-based causation theory, if good, may still give rise to individual specific causation questions relating to knowledge, constructive knowledge and “contributory negligence” style defences.

The third causation mechanism is the US “fraud on the market” doctrine. The doctrine embodies a rebuttable presumption that investors have relied on the integrity of the market price when deciding to purchase on market (Basic Inc v Levinson 485 US 224 (1988) affirmed in Halliburton Co v Erica P John Fund Inc 573 US _ (2014)).[3] On one view it is simply an idiosyncratic US rule of evidence. This is a different concept to inferred reliance and the drawing of “natural” inferences in deceit cases. The US theme is that “the market is performing a substantial part of the valuation process [which would otherwise be] performed by the investor in a face-to-face transaction” (Basic Inc at 244). Of course, the doctrine could only apply to “on market” purchases or “off market” transactions where the market price was the sole price input without any other negotiating influences.

But several points. First, plaintiffs’ lawyers in Australia have generally not relied on this theory, but rather the market-based causation theory. Second, the US doctrine, if applied in Australia, would impermissibly rewrite the statutory causation tests. Relatedly, there is little need to create a new common law evidential presumption. Third, the need for the US doctrine’s creation was an artefact of both the requirement to show reliance under § 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (and rule 10b–5 thereunder)[4] and the restrictions placed upon the commencement of class actions under rule 23(b)(3) of the US Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. A problem had to be solved. Plaintiffs were required to prove a predominance of common issues to get class certification. But reliance is an individual question and necessarily has to be proved in each individual case. Consequently, having to prove reliance on an individual basis results in a predominance of individual issues. Hence, you could not get certification for your class action. Solution? Create the device of the rebuttable presumption. A “commonality of reliance” is then created. Problem solved. But there is no such problem under Part IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). Class actions automatically proceed if s 33C is satisfied. The balancing between common and non-common issues is at most a s 33N question. Moreover, the statutory causation tests do not necessarily require reliance. The US problem does not arise in the Australian context.

Loss and damage

There are various methods for determining the inflationary component, which is relevant to calculating damages, including:

(a) the event study method;

(b) the percentage price inflation method;

(c) the dollar price inflation method.

For the event study method, you take the difference between the predicted price based on the market/industry index and your actual price as the inflationary component of the company’s share price. Moreover, in terms of calculating inflation in the share price from the time when the information first ought to have been disclosed, the divergence of the company’s actual share price from the trend ascertainable from the regression based on the market/industry index over that period will give you the inflationary component.

For the percentage price inflation method, you look at the percentage price drop of the company’s share price at the time of the disclosure of the information. This is then assumed to be the percentage inflation per share for every day of the class period. But this method only works “well”, if at all, in a single disclosure case with no inflation build-up over time. Moreover, it is inadequate because it does not separate out other confounding effects. For the dollar price inflation method, you look at the dollar price drop of the share price at the time of disclosure and take this price decline component as the assumed inflation per share for every day of the class period. Again, this only works, if at all, in the simplified scenario of a single disclosure with no inflation build-up over time. Moreover, it has the same inadequacy in ignoring other confounding effects.

Finally, in addition to these quantitative methods, there are other quantum issues including:

(a) The legal method for quantifying damages and whether it should be:

(i) The difference between the price paid and the true value of the shares at the time of purchase (the classical approach). This may be an approach to use where the contravening conduct caused the plaintiff to acquire shares that would not otherwise have been acquired (the “no transaction” scenario).

(ii) The difference between the price paid and the “but for” market price for the shares that would have prevailed if disclosure had been made, which may be different from the true value. True value may look at the underlying financials of a company to generate a discounted future cash flow valuation, a multiple of earnings valuation or a net tangible assets valuation for the company and, derivatively, share value by dividing the former by the number of issued shares. But the market price would normally be treated as a good proxy for such underlying valuation approaches. This difference between the actual and “but for” prices is the inflationary component discussed earlier. This approach may be suitable where the contravening conduct caused the plaintiff to acquire shares at a higher price than the plaintiff would have acquired them in any event.

(iii) The difference between the price paid and whatever is left in hand after sale of the shares or, if the shares continue to be held through to trial, the difference between the price paid and the true value or market price at the time of trial. There is a problem with (iii). Any share price fall up to the time of sale or the current time (if they continue to be held) may not just relate to the contravening conduct, and hence awarding the said difference may over-compensate the investor. Some plaintiffs have sought to address this issue by pleading and factoring out market movements unrelated to the contravention. Whether they need to do so may be debatable. At one end of the spectrum, you may have a shareholder “locked in” to an illiquid market where there may be an argument for not so factoring this out. At the other end of the spectrum, you may have an investor who deliberately chose to hold and take a further “punt”, so breaking the causal nexus between the contravention and any damage flowing from any further share price fall after that decision. It is difficult to generalise on any proposition in this area. Further, this third approach may be inapposite in any scenario other than the “no transaction” scenario.

(b) Whether the loss of an opportunity to make an alternative investment can be claimed, particularly where an investor, but for the contravening conduct, would not have invested at all in the company’s shares (i.e. the “no transaction” scenario), as distinct from investing in them but at a lower price.

(c) Whether off-setting benefits should be taken into account. Say an investor has several share parcels, and one parcel was bought before the period of the company’s contravening conduct, but was sold during the inflationary period with the investor receiving the “benefit” of the inflation on this parcel. Should this benefit be offset against the losses claimed by the investor on his other share parcels which were purchased at the time when the company ought to have made, but failed to make, the relevant disclosure, and were then held by that investor beyond the inflationary period? Where the investor bought shares during the inflationary period and sold them within that period (assuming the inflationary component to be the same) then there would appear to be no loss. But even this is debatable.

(d) Related to (c), considering how the number and timing of multiple transactions made by each individual investor impact on damages, and applying for each investor:

(i) the “last in, first out” method;

(ii) the “first in, first out” method; or

(iii) the “netting” method.

The “last in, first out” method (LIFO) adopts the approach that the last purchase of shares is treated as the first sold and so on in that pattern. The “first in, first out” method (FIFO) adopts the approach that the first purchase of shares is treated as the first sold and so on in that pattern. The “netting” method involves a “mark to market” approach. In the US, the LIFO method has been preferred; see Pompilio, D, “The Choice Between LIFO, FIFO and Mark-to-Market Accounting in the Estimation of Securities Damages”(2010) 28 Company and Securities Law Journal 243. These questions have not yet been addressed by an Australian court; In the matter of HIH Insurance Ltd (in liq) [2016] NSWSC 482 did not address the matter.

Let me take a simple scenario where during a period X there is a constant inflationary component in the share price caused by a material non-disclosure. Take various scenarios where there is the one parcel of 40 shares bought and sold. First, if you purchased that parcel of shares before period X and sold during period X, then you will have profited by reason of the inflation. Second, if you bought and sold the shares during period X, then you will have gained no profit nor incurred any loss referable to the existence of the inflationary component. Third, if you bought during period X but sold after period X (i.e. when the inflation had been removed from the share price), then you will have suffered a loss by reason of the inflationary component.

Now take a more complicated scenario where an investor has engaged in multiple transactions on a “running” share account. Let me assume the same period X, but this time assume the following. Say 20 shares were purchased before period X (P1), 20 shares were then purchased during period X (P2), 20 shares (from the total of 40 shares) were then sold during period X (S1), and the remaining 20 shares were then sold after period X (S2). What is the profit or loss or net position for our investor referable solely to the inflationary component?

First, assume LIFO is the method. S1 is applied to P2 and because these transactions are both during period X, there is no profit or loss referable to the inflationary component. S2 is then applied to P1, but because both are outside period X, there is no profit or loss referable to the inflationary component. In summary, there is no net change (zero plus zero equals zero).

Second, assume FIFO is the method. S1 is applied to P1. Now prima facie, this shows a profit referable to the inflationary component as P1 was purchased before period X at an uninflated price but sold during period X with the benefit of the inflationary component. Now under FIFO, S2 is then applied to P2. Now prima facie, this shows a loss referable to the inflationary component as P2 was purchased at the inflated price during period X but then sold after the inflation was removed. But in this example there is no net change referable to the inflationary component (profit minus loss equals zero). So, adopting FIFO, you get the same net aggregate result as LIFO, providing you assume that the profit on the shares (P1 “sold” as S1) is taken into account and offset.

What then is the debate concerning the choice between LIFO and FIFO if they yield the same result in the aggregate? Apparently in the US, those who advocate a FIFO approach take the position that the profit on the shares (P1 “sold” as S1) need not be accounted for and offset against the loss (P2 “sold” as S2).

In the real world, where an investor may have multiple transactions, you will not usually obtain net positions of zero referable to the inflationary component. I have just used such an example to show that, mathematically, LIFO and FIFO will produce the same result in the aggregate, unless you exclude in the FIFO scenario profits from the inflationary component of shares sold during the inflationary period allocated against shares purchased before the inflationary period. I have said “in the aggregate”. One can see from the worked examples that LIFO and FIFO may differ with respect to the temporal distribution of profits and losses but not in the aggregate, unless there is the exclusion that I have just referred to. This temporal difference may be of interest to accountants but may have little legal significance in terms of the correct legal method for calculating damages for an investor who has operated a “running” share account.

The “mark to market” approach differs from LIFO/FIFO. At a general level you calculate the change in the value of the investor’s portfolio of shares and cash over the relevant period using actual prices. You compare this with the hypothetical calculated scenario where the prices (purchase or sale) did not contain any inflation. The difference between the actual and the counterfactual constitutes the loss suffered. In this approach, all actual transaction prices are compared to hypothetical inflation-adjusted prices for all relevant purchases and sales. For each date where there is a share transaction, whether sale or purchase, you look at the position with the actual price and work out the total portfolio position and value of all shares using the actual price as at that date (i.e. you mark to market). For each such date, you also undertake the same exercise, but instead of using actual prices you use counterfactual prices with the inflation removed and apply that to the portfolio on that day. For each such date, you compare the total portfolio position comparing the actual (using actual prices) with the counterfactual (prices backing out the inflation) to get the net position attributable to inflation. On some dates there will be losses, on other dates profits. The summing or netting of these profits and losses should yield the net loss due to inflation. The “mark to market” approach is mathematically equivalent to netting.

Cartel class actions

There have only been a handful of cartel class actions launched in the Federal Court, which has exclusive jurisdiction as to the subject matter. These actions present special problems in terms of proof of the effect of cartel behaviour and loss and damage.

There are two contemporary issues relevant to cartel class actions that may be of interest to Australian and UK lawyers being:

(a) first, the use of statistical techniques to assess the existence or implementation of a cartel arrangement and relatedly the calculation of “but for” or counterfactual prices i.e. the prices that would have prevailed in the market absent the cartel conduct; and

(b) second, the consequences for any loss or damages assessment of any pass through mechanism i.e. the scenario where a purchaser passes on to its own customer the effect of any “cartel prices” paid by it to the cartel participant.

Statistical Techniques

In cartel class actions, the principal questions are, first, whether the relevant anti-competitive contract, arrangement or understanding relating to, say, price fixing or bid rigging has been entered into and, second, whether it has been put into effect. Statistical linear regression analysis has been used in cartel class actions to endeavour to answer the second issue and also to provide a basis for inferring the first issue.

Generally, linear regression analysis can assist in inferring causation by at least establishing correlation of movement between two or more measurable quantities. Of course, correlation of movement between, say, variable A and variable B does not of itself prove that one caused the other. There may be an independent cause that commonly caused both A and B to separately move. Correlation of movement may be a necessary condition for causation, but it is not a sufficient condition. But nevertheless, statistical analysis may assist to prove the existence of cartel conduct. Such analysis may show a financial pattern (i.e. trend in prices or profit margins) that is consistent with cartel conduct.

Statistical analysis in cartel cases takes the form of multiple linear regression analysis. In overview, the multiple regression method analyses the relationship between a variable of particular interest (“dependent variable”), for example the price of goods, and other variables that explain movements in that dependent variable over time (“explanatory variables”), for example the costs of producing such goods. An additional explanatory variable (“dummy variable”) is added as the proxy for unexplained factors which may influence the dependent variable. Multiple regressions are then run to see whether the dummy variable has a positive co-efficient. If it does, the co-efficient of the dummy variable measures the extent to which movements in the dependent variable in a given period, say the cartel period, cannot be explained by the usual known influences that are measured by the other explanatory variables.

The co-efficient of the dummy variable is then sought to be associated with the cartel’s effect, as the only factor that could explain the movement in the dependent variable apart from the other known explanatory influences. But the co-efficient of the dummy variable may capture many unmeasurable or unidentified factors (not within the known explanatory variables) that affect price, not just the effect of the cartel. Such other factors may be changes in demand, changes in supply capacity, changes in product quality, new market entry, strategic price setting etc. The influence of these other factors may not be separable from the dummy variable; the positive co-efficient of the dummy variable may represent an indivisible factor, with the “cartel effect” an inseverable (or even non-existent) component thereof. Accordingly, the “dummy” variable, even with a positive co-efficient, may not be able to prove or disprove the existence of a cartel or measure its effects.

Another problem with multiple regression analysis is that it may ignore heterogeneity in the particular products, in the features of the supply relationship between a company and each customer, or in the relevant markets, whether by location, industry segment or time frame. Any regression model is necessarily limited in the supply features it accounts for. The explanatory variables may be limited to cost, location and product end-use, but at a high level of generality and not adequately address the individual factors that determine prices.

Now how does multiple regression analysis work? Let me build this up by the following straightforward steps.

Take the case where you just have one major explanatory variable X (cost) and you are looking at its effect as it changes on the dependent variable Y (price). You first plot a graph for all your actual data for cost (the X horizontal axis) with the corresponding figure for price (at different cost) (the Y vertical axis). You will have a spread of points on your graph. You will not usually be able to join them up with a straight line. But you might imagine that you could draw a straight line running through your dispersed pattern of points, which points would then fall on either side of your imaginary line. More formally, by using “least squares regression” and, more often than not, logarithmic functions for either or both of the dependent or explanatory variables, you can come up with a linear (straight line) relationship, which is a line of best fit, with the equation:

Y = a + bX + u

(where a is the intercept, b is the slope of your line and is known as the co-efficient, u is the random error term, Y is price and X is the corresponding cost).

The line of best fit uses the technique of “least squares”. The values of a and b in the equation are calculated so that the sum of the squared deviations of the points from the line is minimized; this is done through differentiation. Squaring is necessary for each deviation so that you get a series of positive numbers upon which differentiation can operate; if you used non-squared numbers, they would be both positive and negative and would cancel or net out in the sum, thereby giving you nothing mathematically useful to ascertain the minimum. Further, you want to produce a line which minimizes the magnitude of the deviations; the sign of each deviation (+ve or –ve) is irrelevant to that objective. Another reason to square each deviation is that if you have significant outliers, squaring will add weight to their contribution so that large deviations are counted more than small deviations.

Now the straight line is the regression line. If your equation is Y = a + bX + u, you have a regression of Y on X. Your analysis assumes that the X values are correct and derives the Y values from the corresponding X values (Y is “regressed on” X). The analysis also assumes that the reason your Y values in reality do not fall on the line is due solely to random error.

Now b is the co-efficient of your explanatory variable X. If it is a positive number (i.e. the line is upward sloping from left to right), it reflects that as the explanatory variable X (cost) increases, the dependent variable Y (price) also increases. You have a positive linear relationship between the two variables. If the co-efficient is negative (i.e. the line is downward sloping), then there is a negative correlation. If the co-efficient is zero (a flat line), then there is no correlation. So much for the simple case. I have made the assumption that the line, or more correctly, your co-efficient, is statistically significant and has the requisite p value and t-statistic. The p value is slightly counterintuitive. Take the hypothesis that you are trying to prove, say that your result (the co-efficient) is telling you something meaningful i.e. it is not a random effect. Let us assume the null hypothesis (the counterclaim of what you are trying to prove). The p value is the probability of getting the result observed assuming the null hypothesis to be true. If the p value is equal to or less than 0.05, then the probability of observing the result if the null hypothesis was true is less than or equal to 5%. So a p value less than or equal to 0.05 is used to reject the null hypothesis and accordingly to thereby infer that the result observed is statistically significant in terms of some evidence to support the hypothesis contended for. The t-statistic is the ratio of the co-efficient to the standard deviation of the co-efficient (a t-statistic of 1.96 (or higher) corresponds to a p value of 0.05 (or lower)). The intuition is that the lower the standard deviation (i.e. the lower the variance or “volatility” in the measurements) the more statistically significant the line or your co-efficient should be. The lower the standard deviation, the higher the t-statistic. Generally, because linear regression is just a mathematical tool, you can produce such lines for any set of points. But it is only the statistically significant regressions that will be useful. Further, logarithmic functions may be used for your variables as they enable you to deal with rates of change. If rates of change are used (e.g. rate of change in price or cost) and over time you have negative and positive rates of change, the corresponding log measures will be additive or subtractive (as the case may be) and maintain symmetry in the treatment of positive and negative rates of change. That will not be the case if standard arithmetic rates are used.

But in the real world there will be multiple explanatory variables (X1, X2 … Xn) that influence the dependent variable. So your actual equation should look like this:

Y = a + b1 X1 + b2 X2 + … + bn Xn + u